It’s hard to overstate the importance and centrality of Joe Henderson to the music put out on Blue Note Records throughout the ’60s. Appearing on close to 30 records through this period, what is remarkable about Henderson’s output is the sheer range of the music he was a part of: From accessible classics like Lee Morgan’s The Sidewinder, Grant Green’s Idle Moments and Horace Silver’s Song For My Father, to experimental, ‘out’ or otherwise progressive records like Andrew Hill’s Point of Departure, McCoy Tyner’s The Real McCoy or Larry Young’s Unity.

If one looks at Henderson’s discography alone it would seem that he appeared on the scene in ’63 and immediately started making classic, genre-defining records. But of course there is a rich backstory which prepared Henderson for the explosion he would make once he reached NYC: a stint in the US Army where he would tour Europe and cross paths with bebop-meets hard bop pianist Kenny Drew and The Modern Jazz Quartet’s Kenny Clarke. University study during which his classmates included Blue Note labelmate Donald Byrd and legendary pianist and educator Barry Harris. Then, time in the Detroit jazz scene alongside Thad and Elvin Jones, Elvin eventually serving as the drummer on two of Henderson’s most celebrated records (In & Out and Inner Urge).

Henderson’s earliest recordings, beginning with his career-defining debut Page One, are born of his pairing with trumpeter Kenny Dorham. Dorham, thirteen years Henderson’s senior and a staple of the New York scene since essentially the bebop era, played an early mentorship role for Henderson when he moved to New York. The two would go on to feature on a number of each other’s albums on Blue Note, including Dorham’s classic Una Mas. Together they carved out a particular and immediately identifiable mode of hard bop jazz, at once more accessible and memorable than most through the strength of their compositional writing, individual through their respective improvisational voices and exploratory with the license they afforded their bands. Page One is the album most would cite as representing both Henderson and the genre itself in this period, largely thanks to the tunes Blue Bossa and Recorda Me which have become jazz standards. But three months after Page One was recorded, Henderson and Dorham returned to the studio to record Our Thing, an album which understandably lives in the shadow of its predecessor, but one which perhaps pointed more towards the future of the music as a whole.

The programme on Our Thing is expectedly varied but gives a window into the sounds floating around the scene at this time. The Henderson-penned Teeter Totter is a burning 12 bar blues, with a quirky ‘backdoor’ turnaround and a melody that brings to mind George Russell pieces like Ezz-Thetic… a kind of cerebral and modal sound. Henderson’s other tune, Our Thing, is a similarly high energy knotty melody with a form that jumps between double time swing and 6/8 time. Much like Page One, Dorham makes a number of important compositional contributions. Pedro’s Time, Back Road and Escapade all feature lovely 2-horn writing, Dorham perhaps having borrowed some of this from his time with Horace Silver. Escapade is an especially interesting tune with a number of surprising melodic and harmonic left turns over a breezy medium swing. It reminded me of Herbie Hancock’s Dolphin Dance from a couple of years later and it makes for a lovely end to the record.

The most distinctive voice on the record is perhaps pianist Andrew Hill. Jazz piano playing in this period was moving in a number of varied directions, the traces of which are largely evident in the music today. On the one hand, it was becoming formalised and drawing more and more from European classical music thanks to the immense influence of Bill Evans and Herbie Hancock. McCoy Tyner, aside from any specific technical or chord voicing innovations, brought an open and spiritual dimension. Thelonious Monk had already made his immense stylistic mark on the music by the ’60s, though his best selling records were yet to come. Chick Corea and Keith Jarrett were soon to emerge. In a way one can hear pianists grappling with the sound of the ‘new thing’ unleashed upon the world by Ornette Coleman and the question it poses for what the role of the harmonic instrument should be in a style which was unleashing freedom upon the melodic and rhythmic dimensions. Hill’s style can be understood as one potential answer to this question.

There is a sense in which Hill’s style, in this period especially, is a deconstruction of all that came before. You can hear the history of jazz piano in his sound, but in an almost postmodern sense: he runs ‘bebop-like’ lines but not tied to the harmony in any recognisingly bebop way… he uses percussive clustered chord voicings like Monk but he seems to always be working across the beat rather than deeply embedded in it… he simultaneously catches all the hits and wrinkles of a piece when comping, but his solos are often strangely impressionistic.

Hill leaves his mark on the record immediately as the first track Teeter Totter begins with a piano solo. It is a brilliant encapsulation of Hill’s playing: cascades of tonal clusters and broken intervals interspersed with knotty 8th note lines with polyrhythmic left hand accompaniment. Hill is often compared to Thelonious, with the common quote being that he was ‘Monk with technique‘ (I’m certain these people haven’t tried to play a Monk transcription note for note). The superficial similarities are there, but perhaps their greatest difference is the mood they bring to any performance they are a part of. There is a cerebrality to Hill and a grave seriousness he seems to bring to the music, where Monk brought joy and humour. Hill steers the music towards darkness, intensity, conviction and the band seems to embrace it and run with it.

Henderson’s playing is remarkably fully-formed even that this early stage of this career. All his Hendersonisms are firmly in place: the muscular fluency of the faster passages and use of melodic cells and motif development, his use of harmonics and overtones, his perhaps most iconic technique of using of repeated 4, 5 and 6 note groupings in fast flurries. The way he blasts through the title track, with it’s sudden changes from double-time 4/4 to 6/8, points to future players like Michael Brecker and Chris Potter in the way they are able to bend compositional quirks to their will through their sheer force and agility.

Any discussion of tenor saxophonists in this period inevitably invites comparisons with the towering figures of the time. John Coltrane, of course, looms largest, and by 1963, he and his Classic Quartet had already produced several canonical recordings. Wayne Shorter had yet to join Miles Davis or release his most celebrated solo albums, but his work with Art Blakey already marked him as a major voice. Meanwhile, players like Hank Mobley and Sonny Rollins, sometimes unfairly dismissed as ‘lightweight’ for various reasons, seemed to have receded in perceived relevance by this moment. Joe Henderson occupies a particularly intriguing space in this landscape: his records were more accessible than Coltrane’s, but his playing could be every bit as fearsome as Trane or Shorter’s. Within a year, both Henderson and Shorter would take Coltrane’s rhythm section for a spin, on Inner Urge and JuJu, respectively, creating some of the most impactful jazz of the mid-1960s.

On Teeter Totter there is a wonderful series of traded fours between Henderson and drummer Pete ‘La Rocha’ Sims. Not only are Sims’ improvisations wonderfully lucid and his time feel immaculate, but Henderson’s contributions demonstrate how his rhythmic sense is as much part of what makes him compelling as much as his melodic one.

Sims, a little like Joe Chambers, goes under-appreciated compared to the other greats of ’60s jazz drumming. But this record, as well as Henderson’s debut record, are a great showcase of his abilities. He moves with ease between burning swing pieces like Our Thing or Homestretch (from Page One), but particularly thrives on the Latin-infused pieces. This isn’t a surprise given apparently he earned his nickname ‘La Rocha’ from his time playing timbales in Latin bands.

It’s fun to hear how his playing developed in the period between Our Thing and his appearance on Sonny Rollins’ landmark A Night at the Village Vanguard album from 1957. Sims takes an extended solo on A Night in Tunisia which is full of invention and melody, if perhaps a little loose on occasion. By 1963 his sound has truly settled, he incorporates far more bass drum in his phrases and overall seems to have carved out a unique voice. Elvin Jones, who also features on the Rollins record, follows an even more pronounced trajectory. Compare the Vanguard live record to something like John Coltrane’s Afro Blue Impressions live recordings from ’63 and it sounds like a completely different drummer.

Eddie Khan is an interesting inclusion on bass. He does not have an extensive discography, in fact he seems to disappear from the scene by 1965, but he contributes a great deal to Our Thing. On the tune Pedro’s Time especially he plays a very interactive role, mixing walking lines with drones and 5th harmonies. Especially during the piano solo he uses the space to play some very adventurous counter-melodic ideas. His style is well suited to the ‘new thing’, particularly his use of pedals which sounds indebted to Charlie Haden. Khan would go on to appear on a number of future-looking records of the time including a personal favourite, Jackie McLean’s One Step Beyond featuring a young Tony Williams.

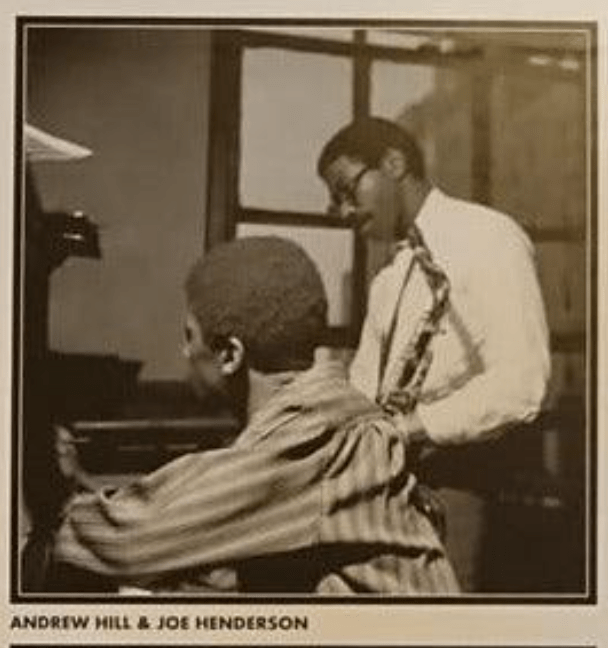

Shortly after this recording session Henderson and Hill would reunite on the pianist’s record Black Fire, probably my favourite of Hill’s. Henderson shows again how well his muscular melodic approach is suited to Hill’s angular and difficult compositions and they would work together again on the celebrated Point of Departure.

Within a year of Our Thing, Dorham and Henderson would go on to record Trompeta Toccata and In & Out, respectively. Though their collaboration was relatively brief in the context of their broader careers, it marked a particularly fruitful period for both artists, yielding a series of vital recordings and enduring standards. Blue Note’s recent release of Forces of Nature, a live session led by Henderson and McCoy Tyner, has prompted a welcome re-evaluation of late-’60s acoustic jazz… a conversation taken up with wonderful insight by Ethan Iverson in his review of the record. I urge anyone reading to return to Our Thing in the same spirit.