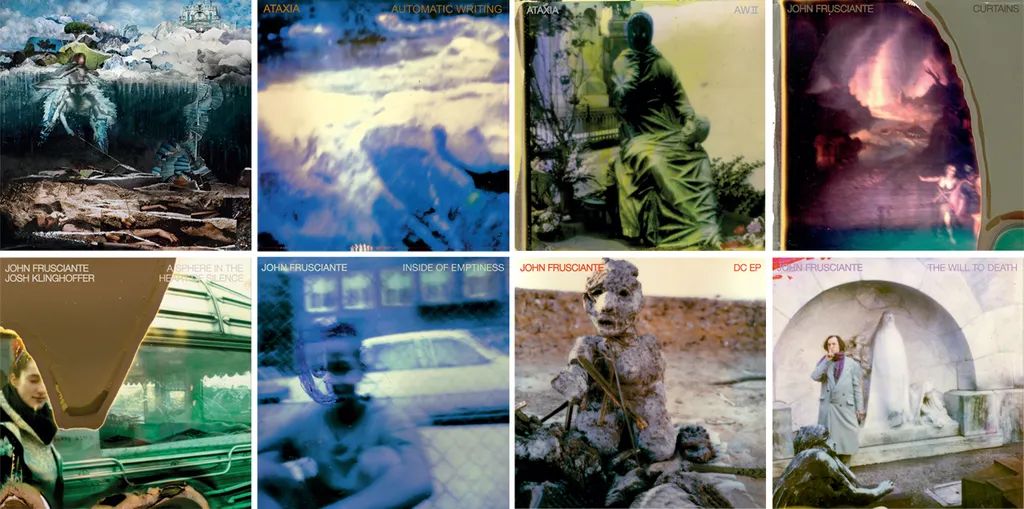

For better or worse, John Frusciante always follows his muse. It led him to join… and then leave… the Red Hot Chili Peppers twice, both times at the height of their superstardom. It led him to follow up the immense mainstream success of the Grammy-winning Blood Sugar Sex Magik with two raw, almost caustic solo records in the ’90s. More recently, it’s taken him deep into challenging hip hop and breakcore-adjacent territory, allegedly going nearly a decade without seriously picking up a guitar. And around 2004–05, it led him to record and release six albums in rapid succession, probably his best work to date, bringing together a set of influences and obsessions he was likely finding hard to express within the Chili Peppers: Bowie/Reed-inspired rock, electronica, Krautrock, garage.

In 2002 the Chili Peppers released By The Way. For non-fans this album probably represents another collection of funky rock songs about girls, California, universal love, girls and California. And yes, it is that. But to less cynical ears By The Way is distinctive in the Chili Peppers catalogue, marking a turn towards greater songwriting depth and sophistication thanks to Frusciante’s outweighed contribution. The album is awash in his Brian Wilson-inspired vocal harmonies. The chord progressions are rich. The tracks are often thickly layered in guitar effects. ‘Writing By The Way has been one of the happiest times of my life‘ he was quoted as saying upon its release. (The feeling wasn’t entirely mutual, Flea saying later he was on the verge of quitting the band due to feeling sidelined by Frusciante’s torrent of creativity during the writing and recording sessions).

Frusciante’s lyrics through this period, in fact beginning with his excellent 2001 effort To Record Only Water For Ten Days, are preoccupied with ideas of being, death, nothingness, rebirth. It is hard to not receive this in the context of his career trajectory, having returned to his most famous band after a number of years in substance abuse-induced exile.

His first musical statement upon his return was the extremely successful Californication. Listening back to it in the context of what was to come shortly after (By The Way and the string of solo records) you can hear Frusciante grappling with his somewhat reduced facility on the guitar, opting for simplicity and immediacy on Californication and tonal texture via effects pedals and layering on By The Way. To his great credit he turned a somewhat diminished virtuosity into some of the most iconic riffs and guitar solos of the period… I would think, for example, many non-fans could hum his three Scar Tissue guitar solos note-for-note.

By the time it came to 2004 Frusciante had regained his facility on the guitar, now with a suite of effects pedals at his disposal, but he had also found his voice. Beginning with Shadows Collide With People, in many ways a continuation of By The Way, and carrying on to The Will To Death, Inside of Emptiness, A Sphere In The Heart of Silence, Curtains, DC EP and Automatic Writing, he embarked on a remarkably lucid, accessible, assured yet still adventurous period of songwriting defined perhaps most of all by the strength of his vocal performances. It seems that he indeed felt reborn, as his lyrics suggested, and was invigorated by these newly honed or rediscovered skills.

Inside of Emptiness might be the most straightforward rock album of the batch. While each album contains a great number of strong songs and memorable moments, it is the nature of such a prolific output that there are some songs which are more impactful than others. Inside of Emptiness, however, feels compelling from start to finish, in part perhaps because it has a unity of focus.

The album begins with What I Saw, which along with songs like The World’s Edge and Emptiness seem like Frusciante’s take on grunge and ’90s alt rock, genres which ran concurrently with his time as a funk rocker. After expressing a distaste for Nirvana particularly in early interviews, Frusciante has since cited Cobain as among his favourite artists. What I Saw especially contains a couple of particularly Nirvana-esque moments, particularly the pre-chorus, but never slips into imitation, especially towards the end where Frusciante gives us one of his signature guitar solos.

Anyone familiar with the Chili Peppers’ live performances during this period, especially the iconic Slane Castle show, would recognise the What I Saw solo as following a similar approach to the one he was using with the Peppers. Frusciante tends to avoid extended, linear melodies, preferring motifs or energetic ‘guitarisms’, often repeating them four times before moving on. Even when he departs from this pattern, his solos are built around motif development, with ideas rarely discarded unless they’ve been fully mined for all their content, energy, or emotion. This gives his solos a ‘hooky’ quality, as opposed to being purely exploratory or self-indulgent. This approach makes perfect sense in a live context, where Frusciante was the sole guitarist, and with no comping behind him, repetitive, rhythmic, and catchy phrases could carry the song on their own.

Songs like Interior Two, A Firm Kick, and I’m Around evoke mid-’60s pop, with The Beatles and The Beach Boys as clear touchstones, but there’s also a hint of ’50s doo-wop. The Velvet Underground also left their mark in two ways: first, in the breezy songwriting style of tracks like Interior Two, which recalls the later VU albums, and second, in the album’s production, which strongly echoes the raw, garage-rock feel of their masterpiece White Light/White Heat.

The album’s centrepiece is Look On, a mid-tempo track that could easily feel like an anthem if not for Josh Klinghoffer’s disjointed, counter-punching drum part (more on his role later). Similar to By The Way’s Don’t Forget Me, it’s one of those slow burners that builds to an almost one-and-a-half-minute guitar solo… arguably one of his best on record. Here, Frusciante steps away from his usual motif development approach, opting instead for a J Mascis-like onslaught of pentatonic melodies and bends. As far as rock solos go it’s a perfect example of how energy, intent, and spirit can elevate even a simple tonal palette into something impactful.

Josh Klinghoffer plays a significant role on the majority of Frusciante’s albums through this period, to the point that the album A Sphere In The Heart of Silence is co-credited to him. Although he is now best known for his decade-long stint as a Chili Peppers’ guitarist himself, replacing Frusciante post-Stadium Arcadium, he is an accomplished musician and collaborator outside of this context. In particular he served as primary guitarist and part-time drummer for PJ Harvey during her Uh Huh Her tour, which was a great live period for PJ.

Klinghoffer, though best known as a guitarist, takes on the role of drummer across this series of albums and does so brilliantly. His playing has the sensitivity of a songwriter, someone who really inhabits the songs, but there’s also a restless creativity in his approach to the kit. He rarely plays a straight beat, constantly breaking things up with open hi-hat stabs and off-kilter fills. One of the real joys of the album is listening to how his drumming locks in with… and sometimes pushes against… Frusciante’s guitar rhythms. Personally, I’ve found the drumming on Inside of Emptiness deeply influential; it’s a rare mix of groove, invention, and just enough disruption to keep things interesting.

It’s interesting to contrast Inside of Emptiness, The Will to Death or DC EP, where Klinghoffer is on drums, with Shadows Collide With People, which features Chad Smith. Smith is, of course, excellent… certainly among the pantheon of great rock drummers… but compared to Klinghoffer, he tends to make safer, more expected musical choices. The result is that Shadows feels somewhat middle-of-the-road… the songs are immaculately played, the production is polished, and Frusciante reportedly laboured over every detail… yet it still comes off somewhat weaker than the albums which followed soon after.

The production on Inside is very minimalistic, reminiscent of the late ’60s to ’70s. What sets it apart is particularly the drum production, which is distorted and dynamic. It reminded me a little of Sleater-Kinney’s The Woods, and in much the same way as it did with Janet Weiss it made Klinghoffer’s drum parts all the more dynamic and exciting.

Vocally, this album captures Frusciante at his peak. By this point, he had a full spectrum of vocal modes at his disposal—soaring falsetto both in lead passages (as on the haunting Scratches) and in layered backing harmonies, alongside his ‘signature’ mid-range vibrato, most memorable on Otherside, the standout from Californication. By 2004, he’d also added a grunge-inspired rasp to his repertoire… a marked shift from the frayed, bleating voice heard on his earliest solo records.

The Red Hot Chili, and by extension Frusciante himself, occupy an odd position for music snob-types (of which I am a card carrying member), perhaps best embodied by an often cited Nick Cave quote, ‘I’m forever near a stereo saying, “What the f##k is this garbage?” And the answer is always the Red Hot Chili Peppers.‘ A little like The Smashing Pumpkins, their combination of a lack of subtlety and an aversion to ’90s style Malkmusian irony make them one of the first artists a budding hipster places in their cordon sanitaire.

Yet what the success of the Chili Peppers allowed Frusciante was the freedom to experiment and follow his muse. Whether it was the psychedelic synthpop of To Record Only Water for Ten Days, the folk rock of Curtains, or the ’60s/’70s-inspired rawness of The Will to Death and Inside of Emptiness, the music he made during this period is both consistently strong and entirely out of step with the trends of its time. It captures a child of Hendrix, Bowie, Iggy… even Elton… rediscovering his love for playing and recording with a vitality not seen since Mother’s Milk in the late ’80s. The musical wanderlust might read as naïve to some… but it was enabled by the unusual privilege of success, allowing him to make records without any real concern for marketability or whether the results came across as too earnest. These albums, and Inside of Emptiness especially, remain rewarding listens even twenty years on.